Technology has a habit of smashing barriers that once seemed insurmountable by bringing advanced capabilities that were the exclusive domain of professionals into the hands of, well, the rest of us.

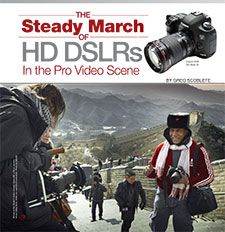

Digital SLRs have been no different. Professional photographers have noted (and lamented) for years how the availability of lower cost interchangeable-lens cameras has introduced a class of “prosumers” who think the defining characteristic of a professional photog is the size of his or her glass. As DSLRs have evolved to record high-definition video, a similar dynamic has taken hold in the video market.

“You can’t be a prosumer without understanding video these days,” observed Chris Chute, research director, Worldwide Digital Imaging, IDC.

“Parts of the production process are now less expensive, and that’s brought more people into the space,” noted Michael Lumpkin, executive director of the International Documentary Association. The public has an insatiable appetite for video and a diverse group of filmmakers has risen to slake this demand. “That’s a good thing in terms of having more voices be heard, but it also dilutes the cash pool” available to invest in new productions, Lumpkin said.

It’s not simply that HD DSLRs are inexpensive enough that a suitably deep-pocketed enthusiast could spring for one, it’s that HD DSLR video quality is so attractive that it’s won over the professionals as well. In a small survey of pro videographers, the market research firm InfoTrends found that a surprising majority (66%) uses DSLRs or interchangeable-lens cameras for their video shoots in addition to traditional video cameras. Two sets of users have converged on DSLR video, and they’re taking it in interesting directions.

How did DSLR video win converts? For many professional videographers, the large image sensor delivered capabilities that traditional video cameras couldn’t, especially a depth of field that replicates the look of a professional cinema camera. As director of photography Erik Naso put it, it delivered a great “filmic look.”

Electronic news gathering (ENG) cameras offered very little in the way of control beyond Iris, white balance, shutter and gain, and everything in the frame was always sharply in focus, noted Michael Artsis, owner of the production company ArtsIsMedia. A DSLR, by contrast, unleashed an enormous amount of control over the final footage. It’s done so at a price that’s much more affordable than traditional cinema cameras.

The large image sensors allowed professionals to gently blur their backgrounds, giving the video a cinematic look without having to rent an expensive cinema camera, added Chuck Westfall, a technical adviser at Canon. The increased light sensitivity of the large DSLR sensor was also appealing to cinematographers who could now do more with natural lighting, he added.

Of course, the price point doesn’t hurt either. “If you don’t have the funds [a DSLR] is an option to create your vision” with a high-quality, cinematic feel, Naso said.

Small Screen Opportunities

While DSLRs have had more than their share of feature film credits, the lion’s share of their work typically appears on the small screen: music videos, TV commercials and for an increasingly video-hungry online media industry.

As DSLR video capabilities have come into their own, some segments of the professional photographic class, such as editorial photographers, are increasingly tasked with assignments calling for both stills and video, observed Ed Lee, group director, Consumer and Professional Imaging Group, InfoTrends. This blending of roles has been driven by a changing media landscape as well, with editorial websites like Vice and Time magazine increasingly diving into long-form video.

“There’s a real appetite now [among online media companies] for long-form, high-quality videos,” noted Shaul Schwarz, a cinematographer. “For me, that’s a very exciting niche.” Indeed, Schwarz’s documentary on the Mexican drug war, Narco Cultura, got its start as a long-form video commissioned by Time. These online videos serve as great art and journalism in their own right but can also serve as a “proof-of-concept” for an idea that can be further developed into a full-length documentary or feature film.

Still photographers can be great filmmakers, Schwarz argued, because “we’ll go further to make the viewer feel closer.” With the right tools, he said, “we can outshine anyone.”

It’s not just professionals who can get in on the action. “You can now be an enthusiast with this technology in a way you couldn’t before—computers have more powerful processing, editing software is more approachable, and with YouTube championing non-cat videos, there’s a growing audience for this kind of high-quality video content,” Chute said. From a user standpoint, he continued, “it’s very exciting.”

Case in Point

To understand how rapid the march of DSLR technology has been in the video market, it’s worth considering the experience of Michael Artsis, a five-time Emmy Award winner and founder of the production company ArtsIsMedia. ArtsIsMedia produces documentaries, news, TV commercials, corporate videos, live broadcasts and infomercials—if it moves, they’ll film it.

In 2010, Artsis was commissioned by the NFL Alumni Association to shoot video at the Super Bowl. One of his videographers had just picked up the Canon EOS 5D Mark III and intended to use it at the gig. Artsis was skeptical, or as he bluntly put it: “I thought he was nuts.” Artsis’s opinion quickly changed in the editing room. “I saw the footage from the 5D, and that’s all I wanted to use. It was stunning.”

A month later, Artsis invested in a 5D for himself and two more for his staff. “I really became a believer.” He knew the trend toward DSLR video had legs when clients asked specifically for their videos to be shot with one.

Now, three years since his first dalliance with DSLR video, Artsis has added Nikon’s D800 into the mix. “I love the fact that you can use the old Nikon lenses with the D800, and the images off this camera are tremendous.” For ENG and video journalists, the D800 gives you everything you need in one package. “It’s versatile and the quality is stunning without being more difficult to use,” Artsis said.

A New Star Is Born?

Just as DSLRs have begun making their mark on the professional video scene, there’s a new technological competitor rearing its head. Or rather, it’s an old dog with new tricks. High-quality cinema cameras have come down in price to the point where they’re starting to contend with digital SLRs for the same video business.

While they’re not (in some cases) able to offer the still photo performance of a DSLR, these lower cost cinema cameras bring the same large image sensors and depth-of-field capabilities that have won DSLRs a following. Plus, these budget cinema cams offer superior audio inputs, and a range of video codecs that professionals prize in postproduction environments. They’re also smaller in size, so small crews, or even lone filmmakers, can use them in settings where a full-blown cinema rig would be less than ideal.

Blackmagic, for instance, has been selling its Pocket Cinema Camera for just $995 (body prices are a bit deceiving, you can easily triple or quadruple the price after lenses, stabilizers and audio). Canon has also pushed into this space with a variant of its 1D camera—the 4K-capable EOS-1D C—as well as the newer Cinema EOS C100 and C300. Despite a narrowing price gap with DSLRs (the EOS C100 costs $5,500 sans lens), there’s still room in the marketplace for both technologies when it comes to professional video production, Canon’s Westfall insists. The professionals gravitating to cinema cameras tend to come from a video background using small chip ENG cameras versus still photographers who are adding video to the mix. The upgrade to a 35mm sensor camera is a large motivator, Westfall said. “They can make their images look more professional.”

For Naso, cinema cameras like the C100 represent fewer compromises. “Having the proper tools built into the body is going to keep me buying cameras that are video specific because the workarounds get in the way of creating compelling images,” Naso explained.

The price is so low that it could have the same revolutionary impact that HD DSLRs did several years ago, Artsis observed. “Anyone willing to put it on their credit can become a ‘professional’ by Monday.”

So are Artsis and his fellow professionals worried about a fresh groundswell of amateur competition? Not so much. The equipment alone doesn’t teach them the most critical element, Artsis said, “and that’s how to tell a story.”